The Post-Journal

by Scott Kindberg

April 7, 2020

Twyman-Stokes Relationship Resonates Now More Than Ever

The date, for one reason or another, hadn’t been engrained in Gregg Bender’s mind.

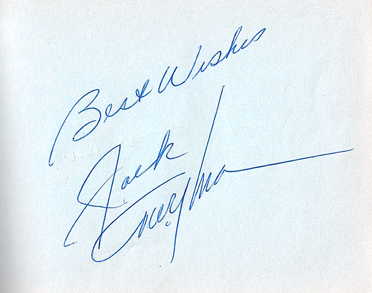

Monday marked the 50th anniversary of the death of Maurice Stokes, an NBA hall-of-fame forward whose paralysis from post-traumatic encephalopathy sparked a legendary kinship with teammate Jack Twyman.

The occasion had nearly come and gone for Bender, a student at Stokes’ alma mater of Saint Francis University, where the funeral was held at the time of his passing.

Rather, April of 1970 was significant to Bender for another reason: his father Robert passed away just three weeks later at the age of 52.

“I never equated the two and here they happened so close to each other,” the Jamestown native recalled Monday.

Bender’s memory was jogged thanks to a powerful Sunday column on the relationship between Stokes and Twyman in the New York Post by my friend and mentor Mike Vaccaro, who thought that bond may be as important of an example now more than ever.

For it was 19 days prior to mourning his own father’s passing that Bender, a junior history major, and his fraternity brothers in the Delta Phi chapter Tau Kappa Epsilon helped to mourn that of Stokes — a founding member of the fraternity’s Saint Francis chapter prior to his graduation in 1955.

“When he passed, the school asked the fraternity if they’d like to participate,” Bender, who graduated from Saint Francis in 1971, remembered. “Obviously, we did and we were very privileged to do so.”

At Saint Francis, Stokes became a college basketball legend: a Pittsburgh-born and Westinghouse High School-bred big man who had led the Red Flash to the semifinals of the 1955 National Invitation Tournament at Madison Square Garden.

“We all knew of Maurice’s legend in school,” Bender said, noting that Stokes had visited a few years earlier for the groundbreaking of the athletic complex that still bears his name.

“We were still a pretty good basketball school back then and so basketball was king,” he said. “We knew all about him.”

That spring, he was picked second overall in the 1955 NBA Draft by the Rochester Royals, who would relocate to Cincinnati in 1957.

His over 16 rebounds per game in 1956 earned him Rookie of the Year honors before setting a league record in rebounds with 1,256 the next season.

During his three seasons in the NBA, he grabbed more boards than any other player with 3,492 while dishing out 1,062 assists in that span, second only to Boston Celtics legend Bob Cousy.

But on the final day of the regular season in March of 1958, Stokes was knocked unconscious after a hard drive to the basket. After being revived with smelling salts, he returned to play in the game, but the worst of that fatal blow was still to come.

Three days later, after an opening-round playoff game against the Detroit Pistons, he became ill while en route back to Cincinnati and eventually suffered a seizure leaving him paralyzed.

With his parents in Pittsburgh unable to care for him, Twyman, his Royals teammate and with whom Stokes had not been particularly close prior to the injury, became his legal guardian for the rest of his life.

Their friendship transcended the sport by which they had been bonded and Twyman helped maintain Stokes’ medical bills thanks to a charity game at Kutsher’s Hotel and Country Club in Monticello, famous for its offseason workforce of NBA superstars such as Wilt Chamberlain and Bob Cousy.

But now, 12 years and three weeks after that fatal trip home from Detroit, such superstars were now en route to the Johnstown Airport, where Bender and his fraternity brothers were waiting for them.

“We basically just did the driving,” Bender said. “A number of private planes came in at Johnstown Airport and we had to drive about 30 miles from campus to pick them up and bring them over to the college. They had the service and then when it was over, they had a reception and then we had to shuttle those back.”

One of the occupants of his vehicle? Oscar Robertson.

“You don’t get to meet or see people like that every day,” Bender said with a laugh. “He was very pleasant. Oscar knew Maurice well.”

Since that day, both Stokes and Twyman have been immortalized in many ways: the latter was enshrined in the Naismith Memorial Hall of Fame in 1983, while the former finally received his well-overdue induction in 2004, with Twyman speaking on his behalf.

And, 50 years later, Robert Bender, too, became immortal as a member of the Chautauqua Sports Hall of Fame for his lauded baseball career at home, as a semi-pro player in the Jamestown MUNY League, and abroad, as a war-league opponent of the likes of Joe DiMaggio, Pee Wee Reese and Phil Rizzuto, among others.

In accepting the honor on his father’s behalf in February, Bender said: “In the movie ‘Field of Dreams,’ Ray Kinsella had a chance to ‘have a catch’ with his father as a way of reconnecting. … This award and speech have been my chance to do the same.”

That bond of both friendship, exhibited by Maurice Stokes and Jack Twyman, and family, exhibited by the Benders, is something we all must commit ourselves to, especially in the days ahead.

And once the world dusts itself off and tries to make sense of all that has occurred in the weeks since this pandemic, my lasting hope is that we all are able to heed the words of Francis of Assisi himself as “instruments of peace.”

“Where there is hatred, let me sow love; where there is injury, pardon; where there is doubt, faith.”

The additional financial assistance of the community is critical to the success of the Chautauqua Sports Hall of Fame.

We gratefully acknowledge these individuals and organizations for their generous support.