The Post-Journal

by Mark Libbon

January 12, 1980

Retired P-J Sports Editor Looks Back As His 45-Year Career Winds Down

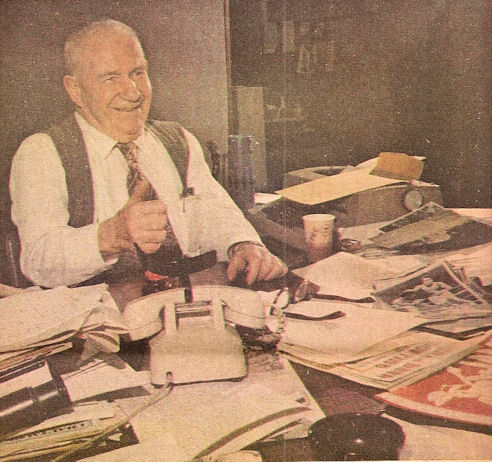

Frank Hyde at his desk before his retirement.

courtesy the Post-Journal, photo by Richard W. Hallberg

His career stats will never be printed on the gray side of a bubble gum card. His signature will not be etched onto the barrel of a baseball bat. And his face is not likely to show up in an Aqua-Velva commercial.

Frank Hyde will never know those rewards of big-time sports. He doesn't care to.

But people in the Jamestown area cannot help but feel they should reward this man for his life's work.

Frank Hyde came to Jamestown in the winter of 1945 with his wife, Evelyn, and their two children. He brought with him a past that was already rich in experience, from poverty and freight trains during the Depression, to carnival wrestling and fight promoting.

He sat down at the sports editor's desk on March 1, 1945 and practically stayed there until last month. (Someone suggested this article should be about Evelyn for putting up with that kind of devotion to the job.)

When he took that seat he ended his career in sports promotion. Since then, The Post-Journal has become widely known for its excellent sports coverage.

His devotion to the job has been admired by readers and co-workers. Big-league ball players don't get up at 3 a.m. every day, but Frank Hyde did, as sports editor, did almost every morning.

His wide knowledge of sports, including a vast memory bank of area residents, is a never-ending source of facts and anecdotes that amaze and amuse.

The best thing about Frank Hyde, some will tell you, is that he has taken the heat from proud parents, partisan players, and zealous fans for 45 years without developing much of a crust.

When local business and sports people held a testimonial for Hyde in 1975, and when The P-J surprised him with a banquet last November, his friends brought out the superlatives they had been saving to honor Hyde's professionalism and good manner.

But they probably got a bigger kick from telling some of the classic stories that reveal the playfulness in their sports editor. One speaker delighted in telling this one, which happened a few years back in the old P-J building:

Stepping away from the sports editor's desk for a few moments, Hyde asked Margie a newsroom secretary and cat lover, to do him a favor.

"Say, Margie," he said straight-faced, "if I get a call from the Falconer firemen, tell them I want the results of their kitten-drowning contest."

"Kitten drowning?" Margie gasped.

Without missing a beat, Hyde explained to the stunned secretary that the contest was merely a convenient way to dispose of surplus cats. The winner, he explained, would be the person who could hold the most kittens in his hands underwater.

Adding a touch of sports irony, he added that last year's champ was not expected to repeat for this year's title because he had lost a finger. He couldn't hold as many kittens, Hyde explained.

As Margie sat in stunned disbelief, Hyde went upstairs and asked the composing room foreman to call Margie with some fake contest results.

After dutifully talking down the information, Margie then dialed the local Humane Society to register a complaint.

The Humane Society, however, was not alarmed – the person who answered the phone asked if Frank Hyde was involved. It was apparently not the first time a kitten-drowning contest had been reported.

"Frankly Speaking," Hyde's regular sports column, reflects his personality the best with its sparkling bits of humor and human interest. In response to news that the average pro football player now earns $70,000, Hyde recently remarked, at the age of 72, Evelyn, find my old shoulder pads."

His "Reports from the Scattergun" follow the progress of local athletes and include notes from people throughout the country who keep in touch with their sports editor.

Now semi-retired at age 73, Hyde continues to write his column and pursue feature stories.

Jim Riggs, Hyde's successor at the sports editor's desk, says he learned more from his mentor than anything in college.

"Most of all," Riggs said he learned, "local news comes first."

"You've got to show concern and you've got to show interest in people and what they are doing," Hyde explained as the bottom line of his business. "You have to be enthused about it, no matter how insignificant it is. That's part of the job."

But as he must show interest in a contest, the sports editor must never show that he is a fan of one team or another. "Above all they expect you to be fair," Hyde said of his readers.

When people feel they have been treated unfairly, they let the sports editor know. From the parent of the kid whose name was left out of the bowling scores to the high schooler whose team was not given a banner headline, Hyde has felt the wrath of the fan.

But he insists, "The paper has always leaned over backward to give good coverage." Whether its pro baseball or local boccie ball, Hyde says, the newspaper will do what it can to promote and report on local sports.

Hyde credits many eager sports-minded people for volunteering their time to promote athletics and competition. The local area, he recently wrote, is "one of the most active home-front sports areas in the state."

"Jamestown, as a whole, is beautiful," Hyde wrote upon his semi-retirement. "I have been many places and am somewhat of an authority on the subject."

Hyde did most of his traveling during the Depression, in what he calls "side-door Pullmans," along with thousands of other men who rode freight trains in search of a living.

"We worked at everything and anything, often for meals and a place to sleep," he recalled. It is difficult, he said, for the younger generation to realize how desperate was the plight of millions in those years.

Born near Jamestown (the one in North Dakota) in 1906, Hyde lived in the north central states during his youth. There he developed a fascination for the old frontier, which he maintains today.

His first contact with the newspaper industry came when he was a 15-year-old copy boy for the Chicago Tribune one summer.

A year later he lived in Yankton, S.D., with his grandmother when two friends offered him a ride to the Jack Dempsey – Tommy Gibbons heavyweight title fight at Shelby, Mont.

A few days before the fight, Hyde was approached by a wire service reporter who asked if the teenager would be a "stringer" for the Yankton Press and Dakotan and provide highlight material to be added to the regular wire service story.

Hyde accepted and phoned in his observations to the newspaper daily. Although the material amounted to notes that ran alongside the main story in the newspaper, one veteran reporter called Hyde the youngest man to ever cover a heavyweight title fight.

Hyde was paid $3 for his contribution and says today, "I would have been glad to do it all for nothing in exchange for a byline."

During the Depression, though, regular jobs were scarce and unemployment benefits were non-existent, so single men like Hyde scrambled to find work whenever possible. Hyde spent a few days as a railroad section worker in North Dakota and became fascinated with telegraphy. With the aid of a night operator, he learned Morse code and was eventually assigned a relief role on a section of track in Montana.

He later took jobs as a timekeeper and part-time motorman at a Butte, Mont., copper mine and as a relief telegrapher for another railroad line.

When those jobs dwindled off, Hyde joined thousands of others "chasing the crops" - haying in Iowa, harvesting grain in Kansas, and picking apples in Oregon and Washington.

He spent part of one summer with Henry Kohlin's wrestling show on the carnival circuit. Having some high school and amateur wrestling experience, Hyde became part of a team that rode into town and met all comers in the ring.

It was not like the acting that goes on in wrestling today, Hyde explained. Anyone who dared would be paid $1 for each minute he lasted with Kohlin's wrestlers, and would earn $25 by pinning one.

"Those hometown men, farmers, ditch diggers, construction workers and cowboys were usually noted for their ability in their area," Hyde recalled. "They came up with blood in their eyes."

Hyde had a few years earlier virtually outgrown an attack of infantile paralysis that left him with a "drop" right foot, as those afflictions were called back then.

After leaving the carnival, though, he sustained a serious hip injury and bade farewell to wrestling.

He settled in Glendive, Mont., where he married the former Evelyn Young in 1935, took a job managing a billiard parlor, and also promoted boxing and wrestling cards. One of the fighters he used, Dick Demaray, a "tough, little southpaw middleweight," lost a bout to Jimmy Clark of Jamestown (our Jamestown), who fought on the U.S. Olympic team in Berlin.

Hyde, the former copy boy and telegrapher, moved back into the communications business when the sports editor in Billings, Mont., was called into the service and said he would not return until after the war.

After several years with the Billings Gazette, the Salt Lake City Tribune and newspapers in Portland, Ore., and Minneapolis, Minn., Hyde and his family packed up their old Dodge and headed east to Chautauqua County.

"We rolled into Jamestown, somewhat dubiously, and were taken in at the first house that had rooms for rent," Hyde said.

The Hydes later gave birth to their third child. Now, Hyde welcomes the opportunity to talk about his children and their accomplishments.

They found the Jamestown area to be filled with warm, outgoing people, and Hyde responded with the same qualities through his sports pages.

Sport Magazine sent its president to Jamestown in 1969 to present its Service Award to Hyde for his contributions to the development and growth of athletic activities.

"Through his sensitive, informative writings over the years, Frank Hyde has been an overall affirmative voice in the community in the field of sports, influencing positively many fine projects in which he was not directly involved," the magazine said.

Hyde voluntarily kept statistics and published records for the PONY baseball league for several years. A co-worker remarked that Hyde strained his eyes and actually damaged his elbow in the many hours he spent working out batting and earned run averages.

He also covered the Jamestown Falcons in spring training for a decade at various Florida sites. (One famous story that several co-workers have urged be related has to do with a toilet, autographed and put on wheels by the newsroom staff, and was sent to Hyde in Florida after he suffered from an embarrassing intestinal problem. Space, however, will not permit a full telling of that tale.)

In his career Hyde has interviewed scores of famous athletes and thousands of not-so-famous. The ones he mentions first are fighters, the "merchants of misery:" Jack Dempsey, Tommy Gibbons, and Joe Louis. Regardless of their standing, however, Hyde believes every person has a story to tell and that other people are what people want to read about.

As one friend explained, though, Hydes's interest in people is partly smart business.

"Frank knows that if you put a Little Leaguer's name in the newspaper, his parents are going to buy the paper, his relatives and his girlfriend will buy the paper, and eventually the kid might subscribe. It's a way of getting them into reading the newspaper."

As those kid-league players have grown up over the years into college and professional ranks, Hyde says, they have been treated to better coaching, equipment and rules.

While sports today are played better than in the old days, he says, the business of sports is over-played.

"When I was a kid, Dempsey and Willard were set to fight in Toledo, and a few days before the match the promoter came up with a contract for them to sign," he recalled. "These days you can't think about a fight until a contract is signed. Ali had five or six lawyers with him the last time he signed one."

"They are pricing themselves out of business," Hyde says of the modern athletic stars. "No baseball player is worth $1 million per year. They hurt themselves because the poor fan is paying the bill."

So in some ways Frank will take the good old days, but overall he believes sports are better organized today and that the promotional spirit that brings the Babe Ruth World Series to town this summer will continue to thrive.

Hyde feels the biggest reward of his job is being able to talk to people and many people are happy for that. A visit to his desk in the sports department might lead to a tale about Casey Stengel's playing days in Wellsville or how his grandmother served breakfast to Jesse and Frank James after an 1871 bank robbery and didn't know it until a posse came by the next morning.

"Sports have been good to me," Hyde wrote in his last column as a full-time sports editor. "I have seen, met, and written about some of the greatest athletes of my day. No one in this business could ask for more."

And no one could ask more of Frank Hyde.

The additional financial assistance of the community is critical to the success of the Chautauqua Sports Hall of Fame.

We gratefully acknowledge these individuals and organizations for their generous support.