The Post-Journal

by Tom Hyde

March 11, 2018

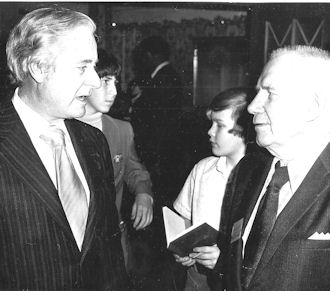

Ex-Sports Editor’s Son Remembers Special Times With His Dad

EDITOR’S NOTE: Tom Hyde, son of former Post-Journal sports editor and 1983 Chautauqua Sports Hall of Fame inductee Frank Hyde, spent much of his youth traveling with his dad to sporting events near and far. Following are Tom’s memories of those special times.

Frank Hyde had bad legs, muscles depleted from childhood polio and an ill-repaired hip broken from wrestling while in his 20s. An injury, I came to believe, from rolling off an elevated ring while entangled with a heavier opponent, both men crashing to a concrete floor, Frank underneath, crushed by their combined weight.

For the record, and from an original poster that’s now a faded piece of family memorabilia, Frank was the “Light Heavyweight Champion of Montana” in an era when wrestling was straight up. Not the phony “showmanship” (his term) it is today. It was based on the classic Greco-Roman style and a wrestler competed using practiced holds and controlled techniques. Referees mattered.

In any event, his polio, combined with the busted hip, made mobility difficult.

He walked with a severe limp, wore supportive shoes and, at times, strapped on leg braces. If he lost his footing and fell, getting up again was next to impossible without something or someone to hang on to.

So perhaps that is why he enjoyed driving.

Being on the road, mobile and free of physical restrictions, he was happy as he could be. Frank loved going places. From the day he took off from his grandmother’s southwest Missouri farm where he was raised, he was a traveller at heart. He was 15. She was living with a man, not his grandfather, who beat him often enough for him to, finally, hit the road.

He continued to travel until he and my mother, Evelyn Young, with my sister Patsy and brother David in tow, settled once and for all in Jamestown, where he was sports editor of The Post-Journal for 38 years. Yet he continued to enjoy the road.

His time spent driving produced talk and stories from his days getting about, wrestling in the 1920s, during the Depression looking for work, moving from one place to another, riding trains, going here and there to places not always clear in my mind but before meeting Evelyn, in 1935, he was often on the move. Joplin, Missouri; Sioux City, Iowa; Chicago; Red Lodge, Montana. Places that resonate with me today from stories he told.

In time, he found work as a telegrapher for the Northern Pacific Railroad and was assigned to a station in Newport, Arkansas where he met Evelyn on a blind date. Stay in Arkansas and settle down? Hardly. They eloped.

They ran off, back to Montana where he had come from. She was only 19 and my understanding is Arkansas law prohibited a woman not yet 21 from marrying without her father’s permission.

And her father would not likely have given it because his wife (my maternal grandmother) had died when Evelyn was still a teenager. Evelyn’s oldest sister had left home and her second oldest sister was bed-ridden with TB, the disease that claimed their mother.

When she met Frank, Evelyn was only 19 but the designated “mother” looking after the home sister and three younger brothers. But she clearly had her own unspoken longing for adventure and Frank must have inspired that.

They were married in Glendive, Montana on September 6, 1935 and soon after he began his career in “newspapering,” as he called it, covering high school football. On June 10, 1936, my sister Patsy was born.

They moved to Billings, where he became the Sports Editor of The Gazette, and where my brother David was born on February 3, 1942 and, finally, for reasons that remain unclear to me today, they made the long drive east to Jamestown, and The Post-Journal. They moved into a gabled house in Celoron, on Chautauqua Lake, which is where I came into the picture. Literally so, as by now Frank had developed a passion for photography, too.

After Patsy graduated from high school, she moved to northern Ohio to room with a girlfriend she knew from home. Frank was not happy seeing his oldest child, and only daughter, move so far away. After all, there was no interstate highway then so getting “out there” in the mid-1950s was a four-hour drive, on Route 20 mainly, stopping at every light, stopping for gas, stopping for “a bite to eat,” as he would say.

But he grew to like making those trips, of getting out of town, of being on the road. He was visiting his daughter and catching up on her new life away from home, but what went unspoken was his joy at driving somewhere, a pleasure no better expressed than with the lighting of a White Owl cigar and, at times, even breaking into song. Typically, an Irish lullaby he knew the tune but not the lyrics from listening to the crooner, Dennis Day, on one of those new LPs Evelyn had bought him for Christmas. On the road, cigar and song, going somewhere, he was a contented man.

Driving for three days to Florida, as he did in the 1950s and 60s, always in April to cover spring training of Jamestown’s minor league baseball team, the cigar and song typically came out on the second day. About the time we were rolling through North Carolina after a long first day and a night’s rest at a motel in Winchester, Virginia.

Frank never owned a new car, his salary did not afford one. However, as Evelyn was working too, she had her own car though she never made the Florida trip herself. Why would she want to go all that way to hang out at a baseball camp?

Evelyn liked baseball, but her job at a bank was more important and because of that we were a two-car family, both Chevys, at one time his a rusty 1955 with a tired engine, hers a newer 1956 with fewer miles and a more powerful engine and certainly more comfortable inside. For the Florida trip, they swapped cars. He would be gone three weeks.

From Winchester, we made our way south to US Highway 1 down to Augusta, Georgia and from there south on 301 to a second night in a motel somewhere near Statesboro.

Up before the sun, as was his usual practice, on the third day we crossed into Florida near Gainesville, passing orange groves, alligator farms, snake farms, souvenir shops selling conk shells, stuff I had never seen before. Florida was exciting. Everything about it was exotic.

Fireworks! Frank would stop to buy fireworks, though often he had done that back in North Carolina, the first state we passed through where cherry bombs, one-inchers and “Chinese fingers” were legal. He got a laugh lighting them with his cigar and, checking first to see there was nobody behind us, watching them explode on the highway in his rear-view mirror.

At some point after reaching Florida, he made a point of stopping for freshly squeezed orange juice. Warm spring temperatures, fresh orange juice and baseball. Life was good. Only at some point south of Gainesville, his mind switched to business and the closer we came to Lakeland, where the Detroit Tigers and their minor league affiliates trained, the more serious he became. Time for work.

He was on the road and away from home, yet the irony was, once he set up in Lakeland he worked longer hours there. Wrote more words and filed more stories. He grew impatient, if not outright angry, with anyone suggesting he was on vacation.

He enjoyed the company of baseball men, current and former major leaguers who were by then managers or scouts with endless stories to tell. He liked meeting rookies who turned up from big cities and small towns across America. Learning where they were from, it was common for him to say something like, “I was there once,” before explaining why. Another story.

His three weeks in Lakeland provided him with more material than the paper could have published in a year. He worked 12-hour days but looking back, I doubt he enjoyed no other time more.

Detroit and its entire farm system trained in Lakeland at a former Army barracks. We were put up in a spacious screened-in room with a cool concrete floor, two single beds and plenty of space for Frank’s desk where he plopped his weighty Remington manual typewriter and quickly established a routine. Even before he unpacked his suitcase he’d be writing.

Breakfast in the cafeteria was buffet style, players had their tables, managers and scouts had theirs which is where we ate every morning beginning at 7. Players were required on-field at 9 after checking a bulletin board for their daily assignment, that is, who was doing what on which of four fields; fields named for Tiger greats Cobb, Greenberg, Gehringer and Cochrane.

Players whose names were left off the daily assignments, but listed on a separate sheet with a heading something like “Report to Office,” knew what was coming. They were going home.

A memory from breakfast: managers and scouts sitting around drinking coffee, Frank is there, I’m next to him on the end seat and a grumpy old-time scout named Wayne Blackburn turns up after a hard night and others tease him, saying, how ya doin’ this morning Blackie?

“*(*)*^(&t,” is all he said, and everyone bursts out laughing.

“*(*)*^(&t,” I said to Frank later, no context, just the word, and I laughed only he told me to stop it, that it wasn’t funny coming from me. Still, it’s been a favorite unspoken curse word of mine ever since.

After breakfast, I followed Frank as he made his way out to the fields where he located the Jamestown team, where his first stop was the manager. One year it was Frank “Stubby” Overmire, a former pitcher for Detroit. His story naturally became one of the first profiles Frank wrote from Lakeland.

Frank wrote about a lot of sports, but baseball stirred him most. At no other time of his life was he more in his element than covering spring training in Lakeland followed by a summer of baseball in Jamestown where, once he negotiated the steps to the rooftop press box, opened his scorebook and lit a cigar, he was ready to play ball.

Other stories from Lakeland, unrelated to the Jamestown team, would develop during our stay. Like a profile of Ed Katalinus, the head scout of the Tigers, an accommodating man who knew more about

professional baseball than anyone in camp. Updates on former Jamestown players who had moved on in the system were common. Random thoughts and bits of information became “Notes from the Scattergun.”

On any given day, an inter-squad game would be played but in any event, after five or six hours on his feet and sitting on team benches, Frank would take his pages of notes and make his way back to the cool shade of our room and begin filing his stories (always more than one) before making his way over to an office phone or into town to Western Union, to send them on to someone waiting at The Post- Journal.

Meanwhile, we came across players not all destined for Jamestown, but names the entire baseball universe would know one day: Denny McLain, Willie Horton, Gates Brown, Pat Dobson, Mickey Lolich, Mickey Stanley, Jim Northrup were minor leaguers one year who just a few years later became World Series champions.

For some, I became a gofer, going for cigarettes and soft drinks, for it was common to see players sitting on a bench during intersquad games smoking and drinking soda. For Denny McLain, the last Major League pitcher to win 30 games in one season, I fetched Camels (only non-filtered in those days). Willie Horton attracted a raft of wisecracks one year when he turned up with his head shaved. It was Gates Brown who became a personal favorite, partly because he was easy going but also because of his name. Gates. I loved that name. Thought for a moment: “Gates Hyde.” But it didn’t have the same ring.

Jerry Klein, inevitably a subject of one of Frank’s reports or columns from Lakeland, was born in Warren, Pennsylvania. Jerry was the Tigers minor league clubhouse manager in Florida, an exceptional man who for years held the same role in Jamestown for the Falcons and then the Tigers, Class A teams affiliated with Detroit.

Jerry was one of baseball’s true characters, an original who drove the player bus in Lakeland, taking players into town for the night, until curfew, and as Frank told it in a column he wrote on Jerry’s passing, in 1973, players were not allowed to bring their cars to camp.

They depended on the bus, only anyone late for the return had to walk the five or so miles back to camp. Jerry wasn’t waiting for them. He was strict about being on time and he played no favorites. One year he did not wait for a top prospect, a future star, who was paid a lot of money to sign.

The kid confronted Jerry at breakfast the next morning only what otherwise might have turned into an ugly confrontation was dealt in a perfect Kleinian way: with poetry.

On the spot, Jerry improvised a poem about a rookie who thought he was too big for his britches, as the saying went, and the result was laughter all around and, from the player, a conciliatory handshake.

Frank had his Jerry Klein stories, too, one he related from a time, presumably, when Frank followed the team bus home from Florida. “The Falcons bus,” Frank wrote, “heading north from training one spring, broke down in a Pennsylvania town. Taking advantage of the two-hour lull in travel, Jerry and I were wandering along the main street window shopping which led me to losing a chicken dinner wager.

“It was a Friday afternoon and the streets were crowded with hurrying shoppers. ‘What do you think would happen if I stopped on a corner and sang my rookie song?’ Jerry asked.

“I advised him to lay off pointing out small-town police are sometimes touchy about visitors disturbing the peace and their slammers are cold, cheerless places.

“Betcha a chicken dinner,” Jerry grinned. At the next corner the round man removed his cap and launched into his rookie song, his bassoon voice echoing up and down the street.

“In a matter of moments, a crowd of hundreds was jamming up the intersection. When Jerry finished, his audience gave him a rousing round of applause, but I was nearly correct about the slammer. A policeman who had untangled the resultant traffic snarl, walked over, halted us and warned: “That was fine, but I need a singing troubadour on my beat like I need a hole in the head.”

I met Jerry for the first time in Florida. He came by our room one day at camp to “borrow your boy,” as he said to Frank. He was off to get oranges from a grove whose owner he knew, who told him to take what he wanted. I went with him in his car and we drove somewhere outside of Lakeland where I picked oranges for the first time.

The trick, he taught me, was to twist them off, not try pulling them off. My hands grew as sticky as they’d ever been, but I had never tasted an orange so juicy and sweet, Jerry telling Frank later that if I didn’t play baseball I would make a great orange picker. He distributed the oranges freely among players with a straight face, telling them, “They’re good for you so make your mother happy,” or something to that effect.

I would take a morning to fill Jerry’s canvas sacks with oranges because I didn’t have much else to do that year but pick oranges and run errands for players. That was not the case another year when I was older and understood to be no longer a gofer, but a prospect attached to the Jamestown squad, even if I was still just 15.

I was given a uniform and like other players told to check the bulletin board to see which field to report to each day. I ate breakfast with players, not at the manager’s table with Frank. I was welcomed by those assigned to Jamestown, namely, a catcher named Don Bryant, who later played for the Cubs and the Red Sox, and a pitcher named Randy Cardinal, who later had a brief Major League career with Houston. Many years later I caught up with Don Bryant for lunch in Los Angeles. By then (he was) a bullpen coach for Seattle.

In Lakeland, at 15, I was unofficial and too young to play, so it meant little more than shagging balls during batting practice and being on a bench during preseason games, looking after equipment and whenever an adjacent field was vacant, as another team might be playing on the road, one player or another might ask me to work with him, like pitchers working on their delivery or catchers working on their throw to second base.

Only just as I was getting used to the routine, things turned sour. One morning I checked the bulletin board and the time slot for Jamestown and the session from 10 to noon that day read: “Manager’s Discretion.”

Vocabulary was not my strength and I was confused, wasn’t sure what to do. Had no idea what “discretion” was. Frank had gone off to file stories, so he wasn’t around. I was alone at the notice board scratching my head and wondering what to do next when Reno Bertoia turned up.

I knew who he was because I had his baseball card. He had played shortstop for the Washington Senators and had been traded to Detroit. As the Major League Tigers had left camp and were by then playing their regular season, Bertoia was, I assume looking back, rehabbing from an injury.

He was the first major leaguer I had ever met in person whose baseball card was among my collection. He wasn’t active that day, so he asked if I wanted to play ping pong. Reno Bertoia asking ME to play ping pong?

There were three tables off a side room from the cafeteria. I was playing ping pong with this “star” (in my eyes) when Frank turned up. He called me over and he was angry. People were looking for me. Why wasn’t I on the field? He had returned from town, walked out to learn no one had seen me that morning. It meant he had to search for me when he had work to do.

He wanted to know what I was doing? Wasn’t it obvious? I was playing ping pong with RENO BERTOIA. I thought he would be impressed, but he wasn’t. The Jamestown manger, Stubby Overmire, was looking for me, others were looking for me, partly concerned, partly (mad) because that morning “Managers Discretion” was a special session for all catchers and I was a catcher.

Frank gave me a solid telling off and I felt ashamed and embarrassed. Didn’t want to show my face the next morning. Stubby, friendly until then, ignored me the next few days. I stood back from the flow feeling small and hating myself and finally hated being there. Hated baseball. Hated Reno Bertoia, who I never saw again.

I eventually drifted back into the routine and though it seemed as if all was forgotten, the whole business disturbed me, and I would take it with me when we left, promising myself never to go back again. And I didn’t, although only because Frank’s spring road trip came to end when Detroit dropped its affiliation with Jamestown. Still, that spring I was playing high school baseball, throwing indoors and moving outdoors after the snow as gone and having been “down there with the big boys,” as he phrased it, my high school coach was impressed enough to promote me to the varsity team my freshman year.

More than any other type of story, Frank liked writing profiles, the stories of others while declining to tell his own, in writing, his own memoir as he was encouraged more than once to do.

Why not? “I’ve done some things I’m not proud of,” he said to me once. Asking him to elaborate was futile. About the only time and place he ever talked about his past was when we were on the road. Travel inspired his personal oral history he would not otherwise have revealed.

He grew up in southwest Missouri, on his grandmother’s farm, in a region billed today as “Jesse James Territory,” for it was there where the brothers Frank and Jesse James, Confederate veterans, sought revenge by robbing banks owned by Yankees.

The James gang rode and robbed and killed but were the Robin Hoods of their day in those parts. One day they turned up at Frank’s grandmother’s house, she a young woman at the time, she not knowing who they were. She offered them food for which they paid handsomely before riding on, before a posse turned up to tell her who the strangers were. Of course, she had not seen them, and the posse rode on, no more informed of the outlaws’ whereabouts than they were before.

It might have been that tale and others like it that inspired Frank, for as he was a traveller he was also a quiet rebel, more than once imagining how one might pull off the perfect bank job. The spirit of Robin Hood dwelled within him, too.

If Frank wasn’t driving somewhere, he travelled vicariously through the pages of National Geographic magazine, one of his favorite magazines. He subscribed. And he wasn’t like most people (myself included) who just looked at the pictures and then put it down again. He may have been the only person I ever knew who read the stories. And they fueled his dreams of travel to far off places, foremost Africa.

Sitting in his easy chair with a stack of National Geographic mags beside him, at one time or another he would have told everyone in the family of his dream of travelling to Africa, going on safari. Only he made it clear he was not a hunter, that his pleasure would derive from photography.

Like travel, photography too was a quiet passion of his. He invariably took his own photos, first from necessity because the newspaper had only two full time photographers and council meetings, car accidents and storm damage were more a priority than sports.

But Frank liked taking his own photos too, and taking a camera to wider world was his dream, inspired by National Geographic and one of his favorite TV shows: Mutual of Omaha’s Wild Kingdom with Marlin Perkins.

Years later, I travelled to Africa and spent 10 days on safari in Tanzania, covering the Serengeti Plain, and taking photos of animals and I have no doubt I was there because Frank was guiding me.

Visits to Patsy in Chagrin Falls, Ohio were often combined with trips into Cleveland for an Indians game. Frank finagled tickets from the team’s press relations manager, who he seemed to know by first name. That’s how my brother and I came to see our first Major League game, for me a moment carved in every American kid’s memory, that one a game between the Indians with Herb Score, Vic Wertz and Rocky Colavito and the White Sox featuring Luis Aparicio, Nellie Fox and Minnie Minoso.

One winter visit to Ohio, Frank secured midfield seats at the stadium in Cleveland for an NFL game between the Browns and the Colts. The Colts were led by their Hall of Fame quarterback, Johnny Unitas, but it was Cleveland’s Hall of Fame running back, Jim Brown who stole the show, running through and over a hapless Baltimore defense.

We drove to Buffalo in September 1958 for another NFL game, a one-off that, for a reason I do not recall, was a “home game” for the Chicago Cardinals who lost miserably that day to the New York Giants, despite some fine running by Chicago star Ollie Matson. Frank’s motive for attending the game: to report on Jamestown native, Jim McCusker, playing his rookie season for Chicago.

We drove to Pittsburgh for the 1960 World Series, the Pirates versus the heavily favored New York Yankees. Frank had gone down alone for Games One and Two in Pittsburgh, but took me along for games Six and, as it turned out, Seven. We stayed at the Mayfair Hotel where an all-night party in the room next door kept us up. Frank did not complain to the front desk because it was World Series time and, after all, people were expected to have fun.

Frank knew the public relations manager for the Pirates, who gave him a Standing Room Only ticket for me. I was 13 and had never been among such a large, frenzied crowd before, including the one permanently entrenched outside Forbes Field.

The SRO gate was far removed from the main gates and that meant I had to negotiate my way out beyond the right field grandstand and back in again through a special gate by which time I was disoriented and had to ask an usher for the door leading up to the press section where Frank would be waiting.

He was relieved to see me and after saying to the minder at the bottom of the steps to the press section, “He’s with me,” and with a well-practiced underhand move slipping the guy a $5 bill, up the stairs we went to a roped off section in the upper grandstand devoted to reporters from all over the country.

Frank took his assigned seat at a bench next to someone from the Baltimore Sun (I checked the guy’s ID) while I squeezed in, off the aisle, next to Frank, until the first inning when an untaken seat two rows below us appeared and where I sat the entire Game 6 watching the Yankees thrash the Pirates 12-0 in a game that felt over before it began after New York scored five runs in the third inning.

From his seat, Frank wrote his story, leaving us, along with other reporters, among the last to leave the ballpark. We returned to Mayfair for room service (another first for me) and trying to sleep over the partying next door.

As any die-hard fan knows, Game 7 of the 1960 World Series was won in spectacular fashion by the Pirates with Bill Mazeroski’s walk off home run in the ninth inning. Dave Schoenfield of ESPN has described it as “the greatest game ever played,” and provides an excellent detailed play-by-play account that can be found online.

That morning, Frank and I left our hotel for the Pittsburgh Hilton, a new luxury hotel in the city’s “golden triangle,” where the Allegheny and Monongahela Rivers merge to form the Ohio. We went there because that’s where the Yankees were staying and, perhaps assuming like most that New York would win Game 7, Frank wanted a few quotes from the manager, Casey Stengel.

The Yankees were the better team, statistically speaking, and the three Series games they had won leading up to G7 were blowouts by a total score of 38-3. We turned up at the hotel lobby to find the players hanging out, waiting to depart for Forbes Field. Little or no security. They were simply part of the crowd, no one bothering them but for a 13-year old from Jamestown wanting autographs.

Casey Stengel stood off to one side with just three or four reporters talking to him. Frank wandered over and joined them. Meanwhile, I carried a World Series record book to collect autographs on. Yogi Berra, Mickey Mantle, Moose Skowron and Tony Kubek signed the book. I was so awestruck in approaching Mantle, I turned speechless, literally, mouth open but nothing coming out and though he gave me a strange look, perhaps wondering if I had a speech problem (and I certainly did at that moment) he signed the book and moved on. Yogi Berra signed the ad on the back page of him promoting Camel cigarettes. He held the book up to others and said something like, “Look at this good- looking guy here.”

Soon the New York team bus pulled up and we watched them roll away to the stadium. Turning up at the ballpark ourselves I felt like a seasoned pro making my way through the Standing Room Only gate and up to the press box stairs where Frank again bribed the same usher to let me through.

As for the game, I can only vaguely recall it being stopped at a routine ground ball that took a bad bounce and struck Yankee shortstop Tony Kubek in the throat, forcing him to leave the game. That bad hop put Pirate runners on base for Hal Smith’s home run giving Pittsburgh its first lead. Forbes Field shook as if it had been struck by an earthquake.

I do not recall the details of the Yankees tying the score at 9-all, only that by then I had returned from a bottom stair (not a seat) along an upper railing, to squeeze in next to Frank when Mazeroski led off the ninth inning and I clearly remember Frank, perhaps knowing it had never been done before, that is, a Game 7 walk off home run, saying, “Boy, what would it be like if he hit one now.”

The Iron City Brass Band played from the top of the Pirates dugout as people danced and streamers and balloons continued to float down and out across the field well after the players had left. I waited for Frank to file his story. It took longer than usual in part because the sports writers that day were no different from the fans. They too were in no hurry to rush off, such was the heightened feeling throughout the ballpark. A major upset had been won, against the odds, like had never happened in baseball before.

It wasn’t a time or a place to rush away from. It was a moment to savor. Years later, photos of people celebrating the end of WWII reminded me of the scene outside Forbes Field that day. It was party time for everyone but the Yankees and their fans, though I don’t recall seeing any.

Once outside, we made our way through the delirious throng to the car and as the sun set on the city, we were on the road again heading north on Route 8 towards Butler, Frank asking me if the Howard Johnson’s (where we had stopped on our way down) was OK for dinner.

Sport is a neutralizer. In the end it doesn’t matter who you are or where you come from, what matters is the willingness to participate and perform to the best of your ability. I learned that from travelling with Frank.

He spoke most contemplatively while driving, his stories reflecting what might loosely be called his philosophy of sport and not once did I ever hear him say anything towards anyone that in today’s world might be understood as “hate” speech.

For Frank, sport was a force for good, a force that united not divided. Our family was never exposed to racist talk or elitist attitudes of any kind because what mattered most to the boss, the sports writer with his working-class sentiment, having known hard times, was not the color of skin or ethnicity or choice of faith or how rich or poor someone was but how they performed on the field or the court or in the ring.

On the road, father-to-son, he had ample opportunity to reveal his attitude towards minorities or women or people of one religious faith or another, but it never happened because that was not who he was. He was a man who appreciated success in sports, no matter who you were.

He was also a man who understood failure and for him losing a game was never the end of the world. There was honor in being there, in trying. It was for Frank as it was for Grantland Rice in that it wasn’t win or lose that mattered most, but how you played the game.

We returned to Pittsburgh in January 1961 for a fight between Cassius Clay and the former NFL lineman, Charlie Powell. Before long, Clay converted to Islam and changed his name to Muhammad Ali but at the time he was still the brash, young Olympic heavyweight champion and “Louisville Lip,” spouting poetry and being outrageous wherever he went. In this case, “Powell would dive in five.”

Frank’s motive for making that drive in winter was twofold. First, it was the first best (and as it turned out only) opportunity for him to see the flamboyant boxer in person. Yet equally motivating for him was that the fight, staged in the new Civic Arena, was in part a fundraiser for miner’s suffering from black lung disease.

Not using his status as a sports editor to get a press pass he bought the best tickets available, putting us ringside among Pittsburgh rich and famous that included some of the Pirates. Dick Groat sat a few seats along.

Frank told me to take my Brownie box camera along. When Ali appeared, Frank elbowed me in the ribs, a nudge, telling me to get up and get a picture, “get right up there by the ring,” I recall him saying in response to my reluctance to move from my seat.

I stood ringside leaning against the structure with my camera poised, looking down through the viewfinder, watching Ali dance away along the ropes and as he turned back I looked up to see him making a silly face at me, a wide-eyed fake surprise that so startled me I didn’t take the picture. He returned to his corner directly above me, my shyness getting the best of me and I returned to my seat. Ali knocked out Powell in the fifth round.

We were back again at the Mayfair Hotel that night only the next morning among the photo spread of the fight in the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette was a photo of me ringside not taking that photo of Ali, the caption reading something like: “Young photographer gets in on the action.” I recall Frank picking up 10 copies of the paper from the hotel newsstand before we headed home.

Frank was loyal to his family, his friends, his newspaper, his town. Yet beneath all of that was a restless spirit of a man who liked going places, too, who liked being on the road, out of town, making new discoveries. A man who appreciated adventure.

On returning from the Peace Corps, where I was assigned to a school to teach English as a Second Language, on a remote island in the South Pacific, I sat on the sofa, clearly recalling him looking at me, smiling, saying “Boy, you’ve had a hell of a time, haven’t you?” It was his way of inviting me to tell him a story or two, only years later, after he was gone, and I was left reflecting on his life, it struck me. I could have said the same thing to him.

The additional financial assistance of the community is critical to the success of the Chautauqua Sports Hall of Fame.

We gratefully acknowledge these individuals and organizations for their generous support.