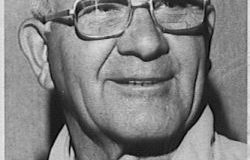

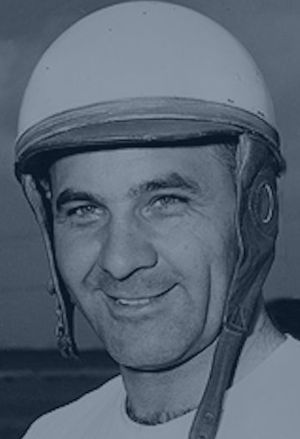

Lloyd Moore

1912–2008

Category

Auto Racing

Year Inducted

2000

Lloyd Dennis Moore was born on June 8, 1912 and he lived his entire life in the same house on the Frew Run Road that his father and grandfather built in the 1890s.

He was the only boy among five children. His father lost a leg just below the knee in a farm accident when Lloyd was 5, so he had to take much of the workload.

Lloyd recalled, “I guess my dad make a poor choice to be a farmer because that put a lot of work back on everyone else after he got hurt. My mother used to get on the hay wagon, and we’d shovel it up to her the best we could.”

He quit high school after a year and a half to help maintain the farm.

For the farm boy from Frewsburg, working on tractors and building jalopies was commonplace. Only after a neighbor argued with him did Moore even think about racing.

read more...

Lloyd liked going fast. "I would run a tractor around the farm at maybe 12 or 13 miles an hour," he said. "Then we raced cars on the roads. There were no speed limits then, so the cops couldn't get us for speeding. They just called it reckless driving."In 1930, Moore got a job with the local school system “haulin’ kids” to and from school in his 1928 automobile, while continuing to work on the family farm. In 1935, he went to work for Leonard Rhodes Studebaker garage on Washington Street in Jamestown “slinging wrenches” for the next 17 years. During that time, he bought his first school bus in 1939 and continued to work for the school system maintaining the buses and delivering students.

He started racing jalopies in 1939 at a track in Onoville called The Dipsie-Do. It was in a little gravel pit on the Frank farm.

Later in ‘39, Lloyd began competing at Satan’s Bowl of Death on the Big Tree-Sugar Grove Road, not too far from the present day Stateline Speedway. Lloyd described Satan’s Bowl of Death as an obstacle course: uphill, downhill, through a stream, and through the woods.

Auto racing was suspended during World War II, but the daredevil nature of Lloyd Moore still surfaced. In 1945, Moore bought a plane. He never took a flying lesson, but he said he learned from a handbook. In his words: “So on my first flight, my nephew wanted a ride. We cranked it up, took off and got up about 100 feet and then motor just quit. We came back down in the woods, chasing the birds right out of the trees. We were lucky to climb out of the crazy thing. I had forgot to turn on the gas. That ended my flying for a while.”

In 1948, Moore resumed his racing career at Penny Royal Speedway, a former half-mile horse racing track in Leon, N.Y. "There were 12 or 15 of us," Moore said. "We paid a $1.50 entry fee and put the money in a hat. That was the prize money. Penny Royal was so dusty you really couldn’t see. I remember there was a maple tree in turn three. When you saw the top of the tree you started turning left, otherwise you’d end up in the cow pasture.”

Moore remembered one race in particular at Leon. "Carl Pintagro drove a Buick as long as a locomotive. He won a race one time with that monster and I chased him home by a close margin. The dust and rocks he dug up showered down on me like a meteor shower. When it was over, my goggles were broken and my head looked like someone had dumped a bucket of blood on me."

Penny Royal Speedway was where Lloyd first met Bill Rexford and developed a friendship with the Conewango Valley driver. That friendship led to Moore’s big break.

One night in August of 1949, as Moore sat in his Frewsburg home, there was a knock at the door. It was Rexford. He was there to borrow Moore's helmet because he had just received an offer to be Julian Buesink's driver at a NASCAR race in Langhorne, PA. Buesink was an automobile dealer from Findley Lake who had a car lot on Fluvanna Avenue in Jamestown.

Buesink and Rexford ran for the first time under the National Association for Stock Car Auto Racing banner at the one-mile dirt oval at Langhorne in September 1949. Rexford brought Buesink’s '49 Ford home in 14th place after starting 23rd. He made $50 in just the fourth race that the NASCAR Strictly Stock Division had ever run.

It wasn't long before Moore, who had torn up his share of dirt tracks in old jalopies, made his move. He, too, approached Buesink about driving one of his cars by talking to Julian's brother-in-law, Clarence Hagelin.

"I said, 'If Julian wants another driver, why I'd be willing to try it,'" Moore said. "It wasn't long before (Julian) stopped by the garage and said, ‘I hear you want to drive one of my cars. Well, I’ve got one for Heidelberg if you’re still interested.’ I said, yah, I’d go there.”

And so Moore did go to Heidelberg becoming a teammate to Rexford.

“I remember getting down there. The car was a standard shift and we had the wrong gear ratio in the rear-end. Julian called back to his shop and told ‘em to get a rear-end out of a car from the showroom floor and have it ready. Julian and I drove the car back home, put a different rear-end in and drove it back to Pittsburgh for the race. Then we drove it home afterwards.

“That was my first NASCAR race, at Heidelberg in 1949. I’ll never forget it. I got my ears pinned back by a girl.”

Moore finished sixth that day, one spot behind NASCAR’s first female racer, Sara Christian, who finished fifth.

"I got raspberries from the guys at the track," Moore said, "and when I got home it was just as bad. Beaten by a woman? Hah, hah."

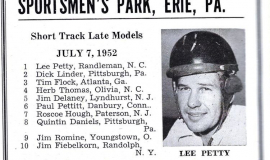

Moore earned $150 for his sixth place finish while Rexford earned $400 for third place behind the winner Lee Petty. It's when the three men from Chautauqua County began a legacy in stock car racing.

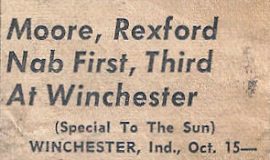

In 1950. Buesink entered Moore in16 of the 19 scheduled NASCAR events. He recorded 7 top-five finishes and 10 top-10 results, finishing fourth in the final point championship tally, earning $5,580. Lloyd’s highlight of the 1950 season was his first and only NASCAR win, a victory in a 200-lap race at Funk’s Speedway, a half-mile oiled dirt track in Winchester, Ind. He wheeled a’50 Mercury from the Buesink stables to the $1,000 first prize money.

The other Buesink driver, Rexford, entered 17 of the 19 scheduled races, recording 5 top-five and 11 top-ten finishes. After the season-long points were tabulated Rexford was declared the 1950 NASCAR champion, while Moore was fourth. Sandwiched in between the two Chautauqua County throttlestompers were NASCAR Hall of Famers Fireball Roberts and Lee Petty.

Julian Buesink, the 1950 NASCAR championship car owner, said his drivers Rexford and Moore couldn't have been more different. "Rexford was pretty careful. He didn't drive too hard and was much easier on a car than Moore was. Lloyd… if you wanted a thrill, come hell or high water, he was going to get to the front. He was soft-spoken, but when you got him on the track he was a different guy."

"We took cars off the showroom floor and drove them to the next race," Moore said. "After the race, we'd drive the car back to Julie's used-car lot. One day, we took Julie's wife's car, a Mercury, and I rolled it over in practice. He got her a new car fast."

"We just stuck a number on the side, took 'em down and raced 'em," Moore said. "NASCAR mechanics today talk about putting in or taking out a half-pound of air to adjust the cars. When we raced, we just made sure we had air in the tires.

The fast driving was not confined to the racetrack.

"After one race, we were driving home on the Pennsylvania Turnpike," Moore said. "Bill Rexford was in front of us and Julie was sitting with me. Julie said, ‘Will this thing go any faster?' So Bill and I started racing side by side on the Pennsylvania Turnpike at 100 miles an hour."

Although Moore and Rexford were teammates they were also competitors. One time they were racing on a one-mile dirt track at the Bainbridge Fairgrounds in Ohio. They were the top qualifiers that day but started at the back for the feature.

Rexford and Moore gradually picked off the entire field and were running first and second with just a few laps remaining.

"I was running second to Bill, just coasting," Moore said. "Pretty soon, I looked in the pits and Julian was out there telling me to go. He wanted me to sic 'em, so I did."

Moore driving a Ford, went right after his teammate in an attempt to win the race. Although, Rexford, in an Olds, held Moore at bay in the final laps, the Conewango Valley driver was furious at what had taken place.

"Bill was mad," Moore recalled. "He said, 'What's the idea of chasing me around like that. You want to smash both of us up?'"

"Julian never batted an eye," Moore continued. "He just said, 'Well, Bill, you came here to race, didn't you?'"

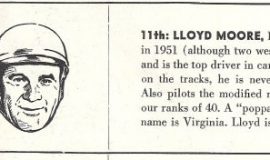

Lloyd became Buesink’s primary driver in 1951 after Rexford left the team. Moore entered 21 of the 33 NASCAR Grand National races and completed the season in 11th place in points. He scored a win at Canfield, OH in the companion NASCAR Short Track Circuit.

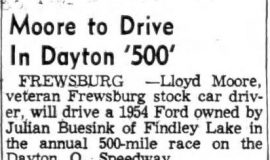

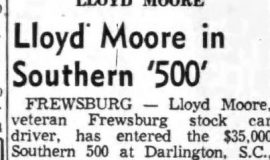

The following year he competed in just 8 NASCAR events. In 1953 and 1954 Buesink turned his attention to the newly formed Midwest Association for Race Cars. Moore drove in 8 MARC races in ‘53 and 10 in ‘54 including a victory in the Metropolitan 300 at Dayton, OH on June 6, 1954.

Buesink and Moore returned to NASCAR for 2 races in 1955 before Lloyd called it quits. "All that gallivanting around the country caught up with me. I never knew where I was going from one week to the next. Wherever Julian said we were going, that’s where we went. I was always leaving my family. This went on for five or six years… going all around the country. It just caught up with me. I just decided one day my family was more important than driving cars in circles. I realized I should be doing more work on the farm. I had a lot of kids to feed and I had a mother and father to take care of. I had been on the road long enough.”

With his driving career at an end, Lloyd focused on his position at Frewsburg Central School as the head mechanic and bus driver until his retirement in 1974. In total, Moore worked 46 years for his hometown school district.

Reflecting on his racing career More stated, "It was quite an experience, sometimes good, sometimes bad, but I loved every minute of it. There were lots of tough guys on the circuit then. Most were short of money and equipment, but tough as all get out when they got behind the wheel of a car."

One of the toughest guys Moore raced against was Lee Petty, father of NASCAR icon Richard Petty, and grandfather to former NASCAR racer Kyle Petty. Lloyd related, "Lee and I were bitter enemies out on the track, but best of buddies when we got off. I first met him at Dayton, OH. It was my first trip to that track and I didn't like the looks of it. Lee came over and said, 'You ain't been around here, have you?' I told him I hadn't. He said, 'Do you want to take my car?' He offered it to me to drive around the track to see what it was like. Lee was a good guy."

Moore recalled another incident with Lee Petty that occurred at the one mile Michigan Fairgrounds track in Detroit. "We were going into the third turn and Lee came up and banged into the back of my car. When the race was over, I went and chewed him out about it and asked him what was going on. He said, 'Oh nothing. It was just an accident on purpose.' Then he smiled. All the Pettys smile.. After that everything was fine."

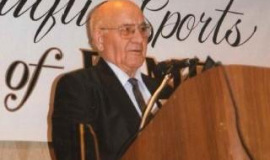

In 2009, the Chautauqua Sports Hall of Fame hosted an event titled “A Night with Kyle Petty” at which Lloyd Moore regaled the young driver with stories about his late grandfather. Kyle Petty so enjoyed his time with “Mr. Moore,” as he called him, that he returned his speaker’s fee to the CSHOF.

One story that Kyle Petty particularly enjoyed hearing was about the time Moore stopped at the Petty home in Randleman, N.C., after a race in the South. Lee and Lloyd ate lunch and then were sunning themselves on the lawn. "I told Lee we had a guy in our garage back home who loves to taste that moonshine medicine. Lee drove me to an open well where there were ropes. He pulled the ropes and up came a basket with a lot of bottles. He gave me one bottle and said to give it to my friend. I did, and when my friend took off the cork and smelled it he said, ‘That's it, all right.’"

Moore was honored for his outstanding auto racing career with induction into the Chautauqua Sports Hall of Fame in 2000.

He was also honored by the Carroll Town Board when it approved the renaming of Myers Street in the village as Lloyd Moore Drive.

Appropriately, the newly renamed Lloyd Moore Drive connects Falconer Street to the bus garage at Frewsburg Central School where Moore devotedly worked for so many years.

Moore was married to the former Virginia Taylor, or “Ginner” as he affectionately called her. They raised six daughters: Virginia, Louella, Mina, Barbara, Linda and Penny.

He was also a lifelong member of his beloved Wheeler Hill United Methodist Church where he served as trustee, treasurer and Sunday school teacher.

Lloyd Moore died on May 18, 2008 at the age of 95. Richard Petty, the King of NASCAR issued this statement: "I was saddened to learn of the passing of Lloyd Moore yesterday. He was a joy to be around. Lloyd was a connection to the origins of NASCAR. Talking to him was like taking a trip down memory lane for me because he raced against my daddy. I still have memories of those races. He would come by the house after a lot of those races because he and daddy were good friends. So I knew Lloyd from the time I was a young kid and I am proud to say we developed a friendship over the years. Lloyd was a great driver and a great person. He will truly be missed."

more about Lloyd Moore

Memorabilia

select an image to enlarge

Photographs

select an image to enlarge

1952 Chrysler owned by Julian Buesink that Moore drove in the

1952 Daytona NASCAR race. He started second and finished tenth.

Note how the front of the car is taped up to protect the paint from

the sand-blasting effect of racing on the beach. Buesink probably

planned to resell the car on his used car lot. The car is parked in

front of a motel where they stayed during their time in FL. They

drove the car back and forth to the race course. They most likely

drove it from Findley Lake to Daytona Beach and back as well.

1952 Chrysler owned by Julian Buesink that Moore drove in the

1952 Daytona NASCAR race. He started second and finished tenth.

Note how the front of the car is taped up to protect the paint from

the sand-blasting effect of racing on the beach. Buesink probably

planned to resell the car on his used car lot. The car is parked in

front of a motel where they stayed during their time in FL. They

drove the car back and forth to the race course. They most likely

drove it from Findley Lake to Daytona Beach and back as well.

Publications

transcribed publications

- Hyde, Frank. "Rexford, Moore Put Jamestown Area on Stock Car Racing Map." Post-Journal (Jamestown), August 8, 1953.

- Hyde, Frank. "Lloyd Moore And His Race Car." Post-Journal (Jamestown), August 31, 1980.

- Courson, Keith. "Leaving A Legacy Of Their Own." Post-Journal (Jamestown), February 16, 1997.

- Sweeney, Steven M. "NASCAR's Great Grandfather." Post-Journal (Jamestown), June 8, 2005.

- Anderson, Randy. "Lloyd Moore, The Oldest Living NASCAR Driver." Post-Journal (Jamestown), December 2006.

- Anderson, Randy. "A Walk Down Memory Lane." Post-Journal (Jamestown), November 11, 2006.

- "Still Going Strong, Moore Celebrates 95th Birthday." Post-Journal (Jamestown), June 9, 2007.

- McShea, Keith. "Moore Still Revving at 95." Buffalo News, August 23, 2007.

- Litsky, Frank. "A Pioneering Driver Spins Tales, Not Wheels." New York Times, May 8, 2008.

- "Lloyd D. Moore (obituary)." Post-Journal (Jamestown), May 20, 2008.

- Peterson, Todd. "NASCAR Pioneer Moore Was Always On The Fast Track." Post-Journal (Jamestown), May 20, 2008.

- Houghwot, Reggie. "Native Son Honored." Post-Journal (Jamestown), March 9, 2009.

scanned publications

select an image to enlarge

Videos

1952 Daytona Beach Race (Grand National Series)

1952 Daytona Beach Race (Grand National Series)

Websites

- "Beyond The Cockpit : World’s Oldest Living NASCAR Driver Shares Memories with Delightful Wit and Down-Home Wisdom." Frontstretch. Accessed December 23, 2018. https://www.frontstretch.com/2007/09/26/beyond-the-cockpit-worlds-oldest-living-nascar-driver-shares-memories-with-delightful-wit-and-down-home-wisdom/.

- "Lloyd Moore." Racing-Reference. Accessed December 21, 2018. https://www.racing-reference.info/driver?id=moorell01.

- "Lloyd Moore." Ultimate Racing History. Accessed January 12, 2021. http://www.ultimateracinghistory.com/racelist2.php?uniqid=1834.

- "Lloyd Moore." Wikipedia. Accessed December 21, 2018. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lloyd_Moore.

- "Lloyd D. Moore." Find a Grave. Accessed November 25, 2022. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/35250254/lloyd-d.-moore.

The additional financial assistance of the community is critical to the success of the Chautauqua Sports Hall of Fame.

We gratefully acknowledge these individuals and organizations for their generous support.